This week, Glenn Williams Jr. taps his equity research analyst background – the land of price-to-earnings ratios and other valuation techniques – to sort out whether bitcoin is under- or overvalued.

Then, Jennifer Murphy, the CEO of Runa Digital Assets, puts digital assets into very broad historical context (the year 1771 gets a mention) and explains how just a few winners tend to drive markets over the long-haul.

– Nick Baker

Let’s Talk About Bitcoin’s Price-to-Earnings Ratio

One of the things I enjoy most about penning this column is the ability to engage with readers and join them on a journey of learning more about this nascent asset class of crypto. Sure I know some stuff, but there is still plenty to explore. Of particular interest to me is tying crypto to my background in traditional finance (TradFi).

I used to be an equity research analyst. My focus was on valuation. I always viewed getting valuation “right” as being of paramount importance and tried to answer two related questions:

If a company was trading below the projected market value, I’d rate it a “buy.” If it was trading above – well, in all candor, I’d usually find another company to cover, rather than rating it a “sell.” A number of dynamics exist in sell-side equity research that lead to those types of decisions, and perhaps I’ll discuss them in a future column.

I employed a combination of fundamental and technical analysis, exploring both absolute and relative valuation techniques. Absolute valuations were based on the level of cash flows that the company was generating, and relative valuations were based on its value relative to a similar entity, or itself at a prior time.

Unlike companies, bitcoin (BTC) and many other crypto assets don’t generate cash flows upon which to base a fundamental analysis. But bitcoin isn’t a company. Bitcoin is a peer-to-peer cash system that allows the transfer of value from one entity to the next, without the need for third party validation. People see value in that, so valuations should be explored.

Given that it has a fixed supply, some also view bitcoin as a hedge against the devaluation of fiat currency or against the actions of inept central banks. I view it as both, as well as a viable asset class where I choose to store some capital.

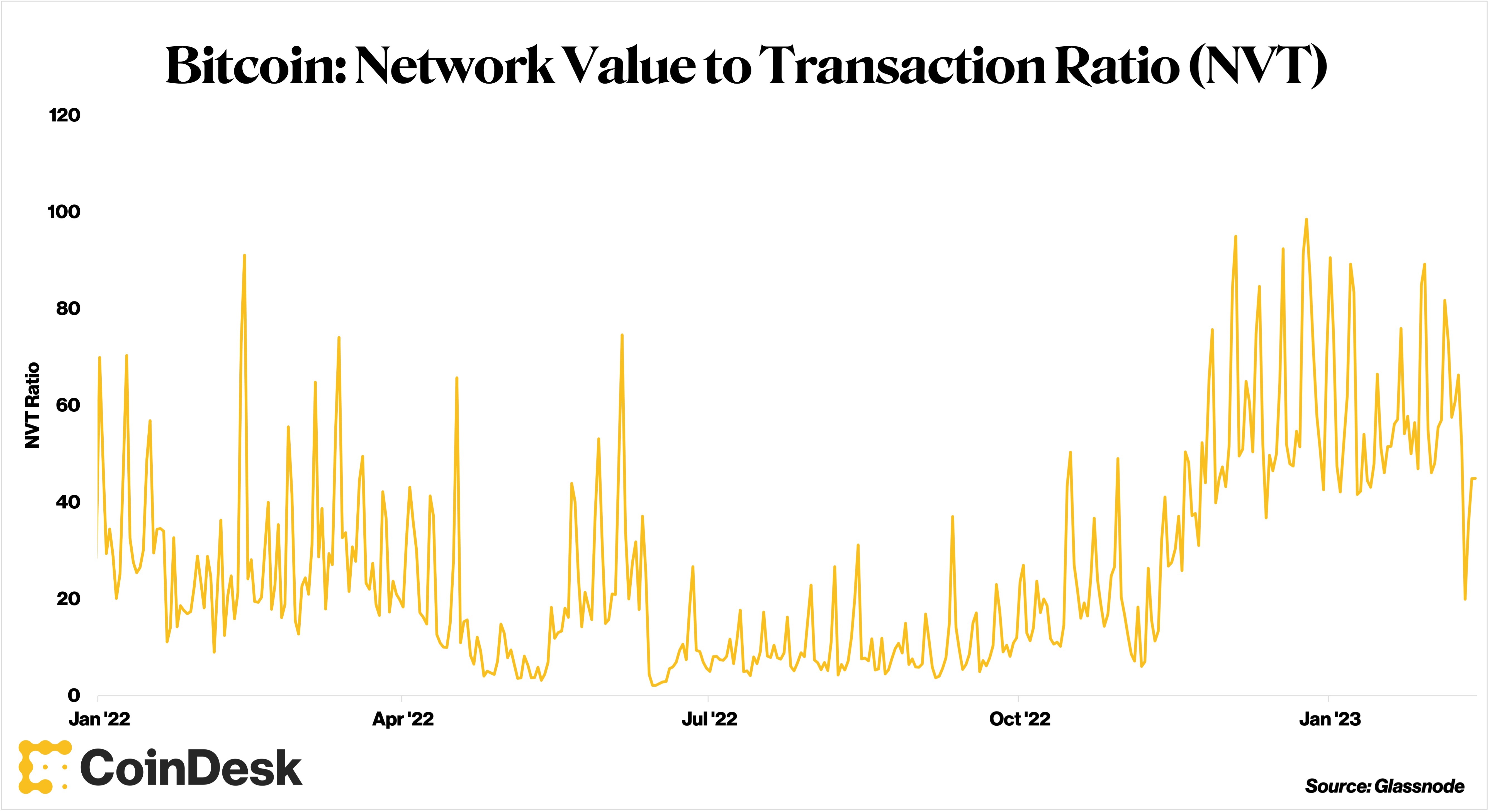

Over in equities, price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios are a common relative valuation metric. There are better valuation techniques, but it provides a quick comparison that tells you how much is being paid for a company versus how much it is earning. The crypto version of P/E is the Network Value to Transaction (NVT) ratio. The metric, created by cryptocurrency analyst Willy Woo, measures the relationship between market capitalization and network transfer volume. Transfer volume is analogous to earnings, and is simply a count of how much bitcoin is moved from one address to another.

In my view, for P/E and NVT to be comparable you must decide that observers value something about both. For companies (and therefore P/E), shareholders value earnings. For BTC (and therefore NVT), it’s the ability to store value in a digital asset, which I view as space on the blockchain itself. And as demand for that space grows, the value of bitcoin increases. If you can get your arms around that, then the NVT ratio is worth including in your analytic framework.

High NVT ratios indicate that investors are valuing bitcoin at a premium. Low NVT ratios indicate the opposite, potentially making a crypto asset alluring to value investors who like to buy things at discounted prices.

But what numbers mean high or low? And when did those readings occur? Given the age of cryptocurrencies, it’s quite possible that what was overvalued in one period, may not be in another. It also makes sense to look at where they are relative to past history. And, once again, it also makes sense to condense it over particular time periods. What is overvalued in one time period may not be in another.

The highest NVT ratio for bitcoin that I found on record was 448.15 on Aug. 29, 2010. Was it overvalued? Well, BTC traded for about 6 cents at the time, and is around $22,000 now, so the relevance of this reading is a bit dubious in my opinion. What if we toss out all data before 2014? That gives a maximum NVT ratio of 98.52, which I think is more sensible. Bitcoin’s lowest NVT on record was 0.22 on Jan. 24, 2016, when BTC was trading at $403. The average NVT over the time span studied was 24, which I also think has relevance.

BTC’s current NVT is 44.89, an 82% premium versus its average since 2014. But it’s at a 20% discount to its 30-, 60- and 90-day moving averages. It makes sense to me that the average premium ascribed to a newer technology like the Bitcoin blockchain, and newer assets like bitcoin itself, would increase over time. It also makes sense to me that its extremes on both the high and low end would narrow, which is what we’ve seen with the data.

Ultimately the position that one takes on the current NVT level will depend on what you anchor to. Those looking over the entirety of BTC’s trading history may see it as overpriced. But a more narrow look shows that BTC may indeed be trading at a compelling valuation.

– Glenn C. Williams Jr., CMT

What Fat Tails and Revolutionary Ages Mean for Digital Assets

Stock market returns are overwhelmingly driven by a small group of winners. We expect the same trend in digital assets.

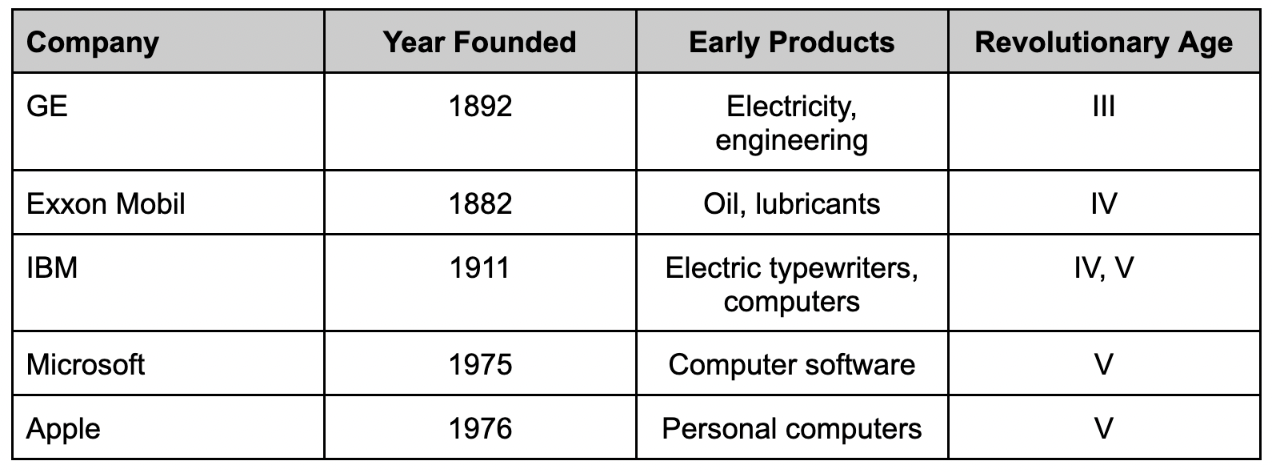

Between 1926 and 2016, just five out of 25,300 publicly traded companies drove 10% of the entire U.S. stock market’s $35 trillion of total wealth creation: Exxon Mobil (XOM), General Electric (GE), International Business Machines (IBM), Microsoft (MSFT) and Apple (AAPL). Ninety stocks accounted for more than half. Just shy of 1,100 generated the entire gain; the rest collectively returned less than U.S. Treasury bills.

Why so lopsided?

Stock returns don’t fall along a normal distribution. They skew positively, with a few remarkable ones creating a “fat” right tail. Long-term investors who didn’t own those stocks risked missing out on the market’s average return.

We anticipate a fat right tail in digital asset returns, too. Bitcoin (BTC) is a great example of a wealth creator. We compared its returns to market-cap weighted portfolios of the top 10, 50 and 100 digital tokens (excluding stablecoins and wrapped tokens) rebalanced monthly over the past five years. None of the broader portfolios outperformed BTC. The 50- and 100-token portfolios lost money over the period.

But why? What causes skewness in the first place?

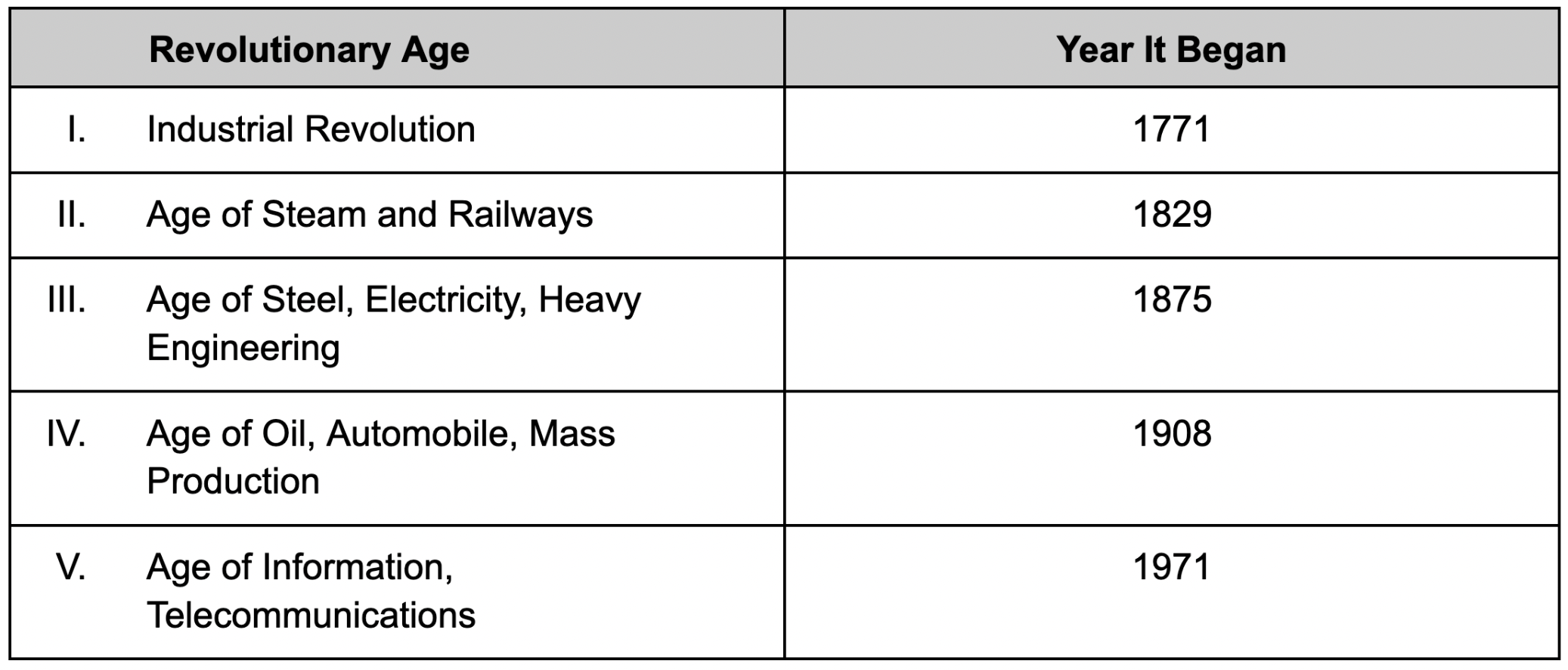

We think a fundamental driver is technological revolutions. In her book “Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital,” Carlota Perez defines these as “a powerful and highly visible cluster of new and dynamic technologies, products and industries capable of bringing about an upheaval in the whole fabric of the economy.”

Perez identifies five technological revolutions since the late 18th century:

Each period begins with disruptive technological innovations that attract talent and risk capital, spawning an explosion of startups. Financial bubbles, corruption and collapse generally follow, eventually bringing regulation, management disciplines and productivity – a golden period of growth and profits. Since the Age of Steel, the golden periods have been dominated by large corporations. The longer the golden period, the greater the opportunity for winners to compound wealth.

Each of the five firms that drove 10% of all wealth creation since 1926 were market leaders of a recent Revolutionary Age:

Notably, each was founded at the beginning of an Age, maximizing the opportunity to compound returns for many years. But just being there wasn’t enough. These winners imagined a future others could not.

We are about 50 years past the dawn of the Information Age. It’s likely a new Age is forming. Will it be the Age of Digital Assets? In our view, digital assets alone are not enough to ignite a revolution. They are, however, a powerful innovation that, together with others such as artificial intelligence, robotics and genomics, have the potential to form a new Age.

If we’re right, the winners of this Age may be among today’s newcomers. Long-term investors would do well to make sure their portfolios include the potential wealth creators that will disproportionately drive market returns in the coming decades. We think digital assets are strong candidates.

– Jennifer Murphy, CFA, CEO of Runa Digital Assets

Takeaways

From CoinDesk’s Nick Baker, here’s some recent news worth reading: