Keynesian economics focuses on using active government policy to manage aggregate demand to address or prevent recessions.

Keynes developed his theories in response to the Great Depression and was highly critical of earlier economic theories, which he called “classical economics”. Activist fiscal and monetary policy are the primary tools Keynesian economists propose for managing the economy and tackling unemployment.

What is Keynesian Economics?

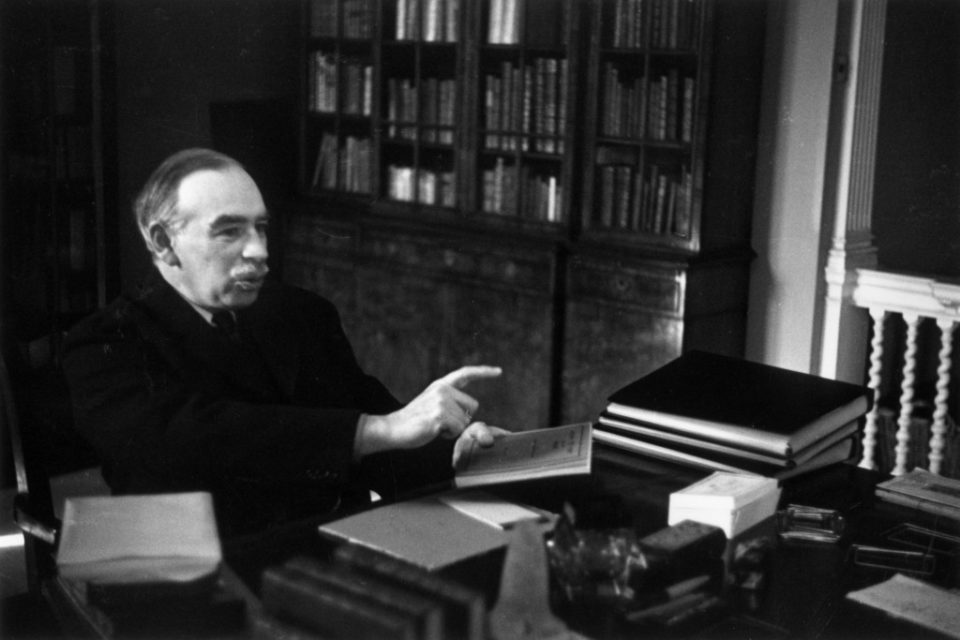

Keynesian economics is a macroeconomic economic theory of aggregate spending in the economy and its effects on output, employment and inflation. Keynesian economics was developed by the British economist John Maynard Keynes in the 1930s to understand the Great Depression. Keynesian economics is considered a “demand side” theory that focuses on changes in the economy in the short run. Keynes’s theory was the first to sharply separate the study of economic behavior and markets based on individual incentives from the broad study of national economic aggregate variables and structures.

Keynes, based on his theory, advocated increased government spending and lower taxes to stimulate demand and pull the global economy out of depression. Later, Keynesian economics was used to refer to the concept that by influencing aggregate demand through government’s activist stabilization and economic intervention policies, optimal economic performance could be achieved and economic collapses could be avoided.

Understanding Keynesian Economics

Keynesian economics represented a new way of looking at spending, output, and inflation. Previously, what Keynes called classical economic thought argued that cyclical fluctuations in employment and economic output create opportunities for profit that individuals and entrepreneurs will encourage to pursue, and in doing so correct imbalances in the economy. According to Keynes’ construction of this so-called classical theory, if aggregate demand in the economy falls, the resulting weakness in production and employment will accelerate a fall in prices and wages. A lower inflation and wage level will encourage employers to make capital investments and employ more people, stimulating employment and restoring economic growth. Keynes believed that the depth and persistence of the Great Depression severely tested this hypothesis.

Keynes, in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest, Money, and Money, and other works, opposed classical theory construction, saying that during recessions, business pessimism and certain features of market economies would increase economic weakness and cause aggregate demand to fall further.

Keynesian economics, for example, opposes some economists’ idea that lower wages can restore full employment because labor demand curves slope downward like other normal demand curves. Instead, he argued, employers would not add workers to produce goods that could not be sold because demand for their products was weak. Similarly, poor business conditions may cause companies to reduce capital investment rather than take advantage of lower prices to invest in new plant and equipment. This will also have the effect of reducing overall spending and employment.

Keynesian Economics and the Great Depression

Keynesian economics is sometimes referred to as “depression,” as Keynes’s General Theory was written during a period of deep depression not only in his homeland of the United Kingdom but worldwide. referred to as “the economy”. The famous 1936 book was shaped by Keynes’s understanding of the events that unfolded during the Great Depression, which he believed could not be explained by classical economic theory as depicted in his book.

Other economists have argued that after any widespread downturn in the economy, businesses and investors who take advantage of lower input prices for their own benefit will bring output and prices to a state of equilibrium unless otherwise prevented. Keynes believed that the Great Depression opposed this theory. Output was low and unemployment remained high during this time. The Great Depression encouraged Keynes to think differently about the nature of the economy. From these theories, he built real-world applications that could have implications for a society in economic crisis.

Keynes rejected the idea that the economy would return to a state of natural equilibrium. Instead, he argued, when an economic downturn begins for whatever reason, the fear and gloom it creates among businesses and investors will tend to be self-fulfilling, leading to a sustained period of recession and unemployment. In response, Keynes advocated an anticyclical fiscal policy in which during times of economic distress the government should assume deficit spending to compensate for the decline in investment and increase consumer spending to stabilize aggregate demand.

Keynes was highly critical of the British government at the time. The government greatly increased welfare spending and increased taxes to balance the national books. Keynes said this would not encourage people to spend their money, thus leaving the economy sluggish and unable to recover and return to a successful state. Instead, he suggested that the government spend more money and cut taxes to cover a budget deficit that would increase consumer demand in the economy. This, in turn, will lead to an increase in overall economic activity and a decrease in unemployment.

Keynes also criticized the idea of excessive savings unless it was for a specific purpose, such as retirement or education. He saw this as dangerous for the economy because the more money stagnated, the less money there would be to stimulate growth in the economy. This was another of Keynes’ theories for preventing deep economic depressions.

Many economists criticized Keynes’ approach. They argue that businesses that respond to economic incentives will tend to return the economy to a state of equilibrium unless the government prevents them from doing so by interfering with prices and wages and making the market appear to be self-regulating. On the other hand, Keynes, writing as the world plunged into a period of deep economic depression, was not so optimistic about the natural balance of the market. He believed that government was in a better position than market forces when it came to creating a sound economy.

Keynesian Economic and Fiscal Policy

The multiplier effect developed by Keynesian student Richard Kahn, Keynesian It is one of the main components of the anticyclical fiscal policy. According to Keynes’ theory of fiscal stimulus, the injection of government spending eventually leads to additional business activity and even more spending. This theory suggests that spending increases total output and generates more income. If workers are willing to spend their extra income, the resulting growth in gross domestic product (GDP) may be even greater than the initial stimulus.

The size of the Keynesian multiplier is directly related to the marginal propensity to consume. Its concept is simple. Spending from a consumer then becomes income for a business that spends it on equipment, worker wages, energy, materials, services purchased, taxes, and investor returns. This worker’s income can then be spent and the cycle continues. Keynes and his followers believed that in order to effect full employment and economic growth, individuals should save less and spend more, increasing their marginal propensity to consume.

In this theory, one dollar spent on fiscal stimulus eventually creates more than one dollar in growth. This seemed like a blow to government economists, who could provide justification for politically popular spending projects on a national scale.

This theory was the dominant paradigm in academic economics for decades. Finally, other economists such as Milton Friedman and Murray Rothbard showed that the Keynesian model misrepresents the relationship between saving, investment and economic growth. While most economists agree that the fiscal stimulus is far less effective than the original multiplier model suggested, most economists still rely on multiplier-generated models.

The fiscal multiplier commonly associated with Keynesian theory is one of two broad multipliers in economics. The other multiplier is known as the money multiplier. This multiplier refers to the money creation process resulting from the fractional reserve banking system. The money multiplier is less controversial than its Keynesian fiscal counterpart.

Keynesian Economic and Monetary Policy

Keynesian economics focuses on demand-side solutions to periods of recession. State intervention in economic processes is an important part of the Keynesian arsenal in tackling unemployment, underemployment and low economic demand. The emphasis on direct government intervention in the economy pits Keynesian theorists against those who advocate limited government involvement in markets.

Keynesian theorists argue that economies do not stabilize themselves very quickly and need active intervention in the economy that increases short-term demand. They argue that wages and employment are slower to respond to market needs and require government intervention to stay on track. They also argue that prices are also unresponsive and only change gradually when monetary policy interventions are made, giving rise to a branch of Keynesian economics known as Monetarism.

If prices are slow to change, this makes it possible to use the money supply as a tool and to change interest rates to encourage borrowing and lending. Lowering interest rates is a way for governments to intervene in economic systems in a meaningful way, thereby stimulating consumption and investment spending. Short-term demand increases triggered by interest rate cuts stimulate the economic system, reinvigorating employment and demand for services. New economic activity then fuels continued growth and employment.

Keynesian theorists believe that without intervention, this cycle is broken and market growth becomes more volatile and prone to extreme volatility. Keeping interest rates low is an attempt to revive the economic cycle by encouraging businesses and individuals to borrow more. They then spend the money they borrowed. These new expenditures stimulate the economy. But lowering interest rates does not always lead directly to economic recovery.

Monetarist economists focus on managing the money supply and lowering interest rates as a solution to economic woes, but generally try to avoid the zero-bound problem. As interest rates approach zero, it becomes less effective at stimulating the economy by lowering interest rates because it reduces the incentive to invest rather than simply holding money in cash or close substitutes such as short-term Treasury bonds. If interest rate manipulation fails to stimulate investment, it may no longer be sufficient to generate new economic activity and any attempt to achieve economic recovery may stop altogether. This is a kind of liquidity trap.

When lowering interest rates fails, Keynesian economists argue that other strategies should be used, primarily fiscal policy. Other interventionist policies include direct control of the labor supply, changing tax rates to indirectly increase or decrease the money supply, changing monetary policy, or putting controls on the supply of goods and services until employment and demand are restored.