Ethereum’s upcoming Merge could make the second-largest blockchain greener, faster and cheaper. But a law professor says it could also create regulatory headaches by transforming ether (ETH), the network’s native asset, into a security under U.S. law.

“After the Merge, there will be a strong case that ether will be a security. The token in any proof-of-stake system is likely to be a security,” tweeted Georgetown Law professor Adam Levitin on July 23.

If Levitin is right, and, more importantly, if the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) shares his view, exchanges that list ether (and that would be nearly all of them) would be subject to more onerous regulatory requirements. Like the bitcoin (BTC) cryptocurrency, ether has until now been treated as a commodity, outside the SEC’s jurisdiction.

Most chatter in the Ethereum ecosystem has concerned technical aspects of a post-Merge proof-of-stake network rather than such legal questions. Goerli, a software update expected to take place Wednesday, is the final test before the second-largest blockchain fully transitions from the more energy-intensive proof-of-work to proof-of-stake. The switch is expected to be complete by October.

Read more: Goerli Is Coming: Ethereum’s Last Rehearsal Before the Merge

Levitin’s argument is anchored in the Howey Test – detailed in a 1946 U.S. Supreme Court ruling often used to determine whether an asset is a security. To fully appreciate Levitin’s perspective, it’s important to understand Howey and the concept of staking in a proof-of-stake system.

Staking

Proof-of-stake is a consensus mechanism that allows all nodes on a blockchain to agree on the state of a network. It requires nodes called validators to propose and validate new blocks. Validators must pony up capital for a chance to participate in this process (whereas proof-of-work, the mechanism Ethereum is replacing, requires mining nodes to expend energy as they compete to find or “mine” the next block). This investment of capital is called staking.

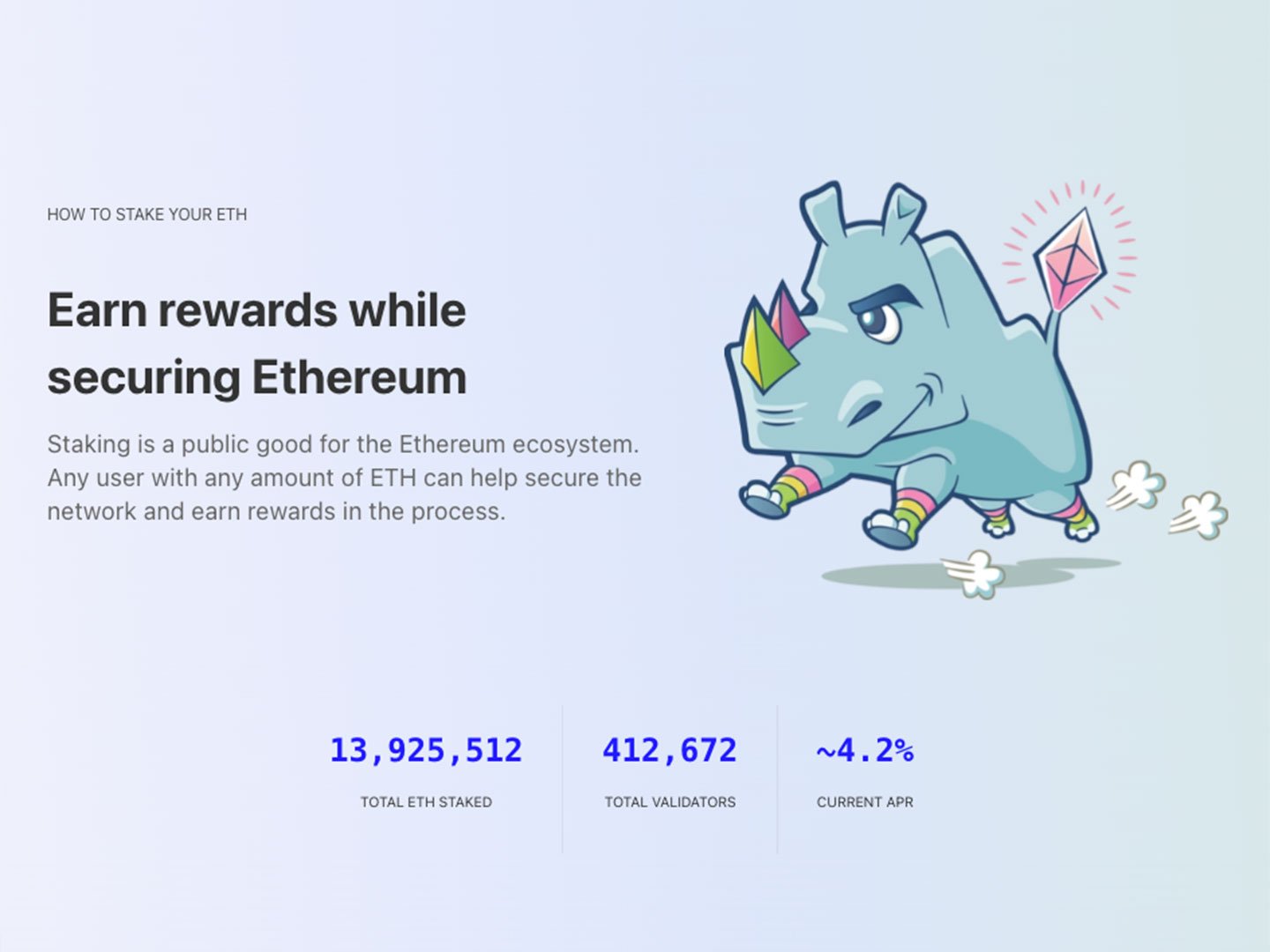

A screenshot of the Ethereum Foundation’s staking web page (Ethereum Foundation)

Read more: What Is Staking?

The minimum staking requirement for Ethereum validators is 32 ETH, which is equivalent to roughly $53,000 as of this writing. The incentive for staking and investing hardware and software resources into a network is to earn rewards. According to the Ethereum Foundation, the nonprofit that guides software development for the network, validators can currently earn about 4.2% annually. For perspective, that’s nearly double what a one-year certificate of deposit (CD) from a typical U.S. bank would pay.

Validators are randomly chosen to propose and validate blocks. The higher the amount of staked ETH, the higher the probability of being chosen and rewarded (Ethereum has over 400,000 validators on its fledgling Beacon Chain). In other words, the more you stake, the more you make.

Read more: Proof-of-Work vs. Proof-of-Stake: What Is the Difference?

William John Howey

Let’s review the history and mechanics of Howey to understand Levitin’s argument.

William John Howey was born in southern Illinois in 1876. He eventually moved to Lake County, Florida, where he became a successful real estate developer and politician. He specialized in growing and selling citrus fruits. Howey also sold land sales contracts for citrus groves. Half of his land was for commercial use while the other half was divided into tiny strips and sold to the public.

William John Howey (Howey.org)

He founded the Florida town of Howey and became its mayor in 1925 (after which it was renamed Howey-in-the-Hills). He built a couple of hotels and an iconic mansion (now a popular wedding venue). Visitors to the little resort town would stay in Howey’s hotel right next to the citrus groves. Anyone who inquired about the groves became a potential town of Howey-in-the-Hills investor. These prospects were pitched on buying the land from Howey’s companies.

Part of the purchase agreement was to have Howey’s companies develop and service the acquired plot in order to grow and sell citrus fruits for profit. Profits would then be split between Howey’s companies and its investors. Howey died in 1938, but his companies carried on.

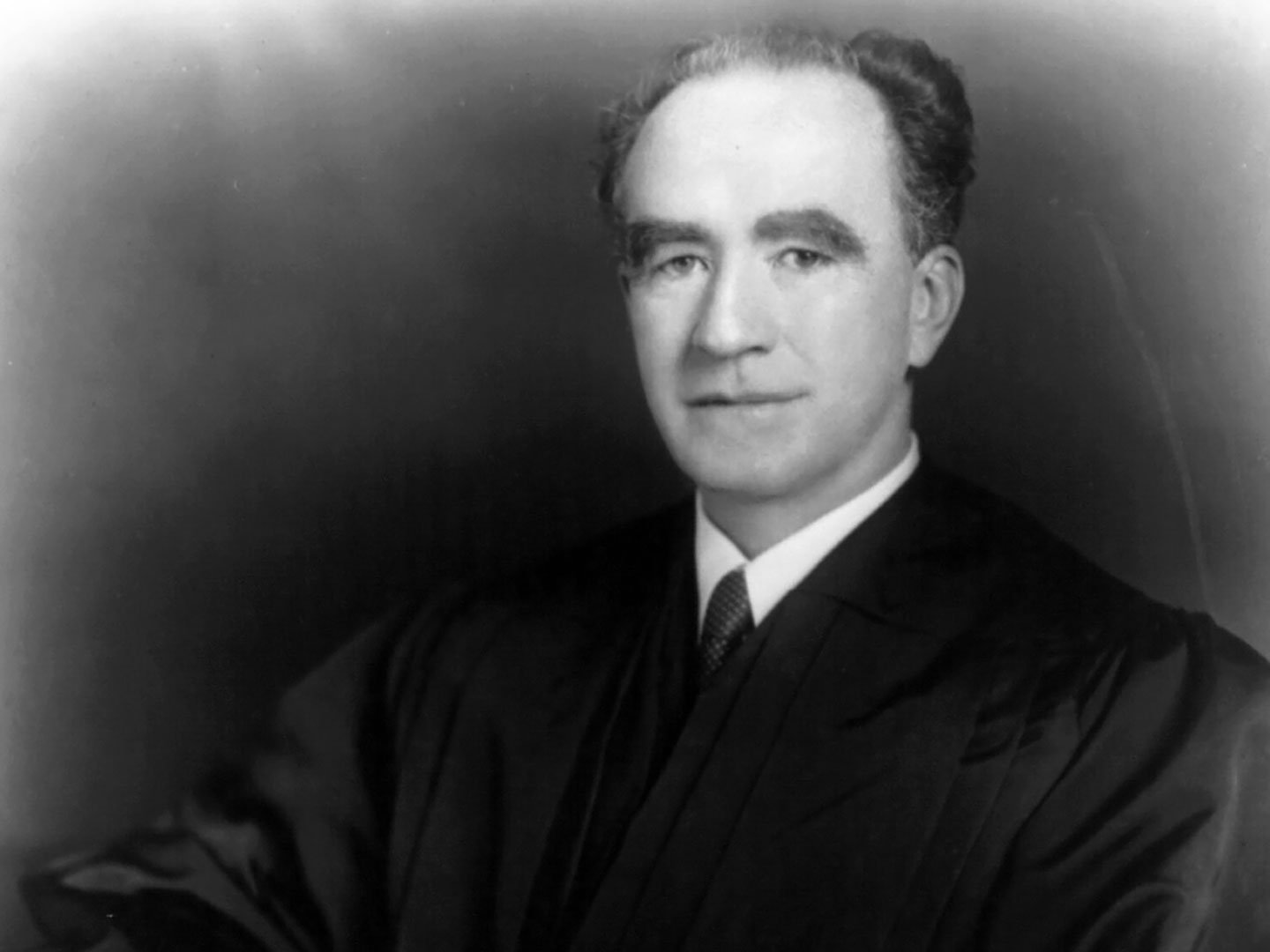

A few years later, the SEC accused the companies of selling unregistered securities. The case was eventually brought before the U.S. Supreme Court in May 1946. Writing for the majority, Justice Frank Murphy determined that Howey’s land sales contracts qualified as securities in the form of investment contracts as per the Securities Act of 1933.

The Howey Test

In his opinion, Justice Murphy took it upon himself to craft a definition of the term “investment contract” (the term is used but not defined in the law). An investment contract means a contract, transaction or scheme whereby a person invests his money in a common enterprise and is led to expect profits solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party.

Justice Frank Murphy of the U.S. Supreme Court Date: 1940s (Wikimedia)

The definition has four distinct components, or “prongs”:

1. An investment of money

2. In a common enterprise

3. With an expectation of profits

4. Solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party

If an asset meets these four criteria it’s deemed an investment contract and thus a security. Even if an asset doesn’t quite meet the criteria, it may still be deemed a security based on economic realities – the totality of circumstances under which a business transaction occurs.

Read more: A ‘Howey Test’ for Blockchain? Why the SEC’s ICO Guidance Isn’t Enough

Adam Levitin’s argument

Levitin argues that a proof-of-stake system like Ethereum requires an investment of money (staking) in a common enterprise (Ethereum) with an expectation of profits (staking rewards) primarily from the efforts of others (other Ethereum participants).

He uses the phrase “primarily from the efforts of others” instead of Justice Murphy’s “solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party.”

“Courts of Appeals have read ‘solely’ as being more like ‘primarily’ or ‘significantly,’” Levitin wrote.

However, Levitin acknowledges the significance of the latter part of Justice Murphy’s definition which references a “promoter” – the third-party entity shilling the investment contract and responsible for most of the profit-generating activity. Who would that be in the Ethereum ecosystem?

“None of this answers the trickier question of who the ‘issuer’ is when you’re dealing with a decentralized system. But that’s part of the broader problem of how to fit decentralized systems into a person-based legal system,” Levitin tweeted.

Counterarguments

Whodunit?

The most convincing counterargument to Levitin’s position may be the one he alluded to himself. If Ethereum is a truly decentralized network, who’s the third-party promoter? Former SEC regulator William Hinman’s comments in 2018 seem to undermine ETH’s risk of being branded a security on this basis.

“As a network becomes truly decentralized, the ability to identify an issuer or promoter to make the requisite disclosures becomes difficult, and less meaningful,” Hinman said. He was the SEC’s corporation finance director at the time. However, the SEC has not referenced nor acknowledged Hinman’s remarks since he made them.

What pool?

Levitin pointed out that proof-of-stake allows stakers to invest in validation pools where others perform the actual hashing, or processing transactions using a cryptographic algorithm. This goes back to his interpretation of the third and fourth prongs of Howey – expecting profits from the efforts of others.

Tim Beiko, who runs protocol support for the Ethereum Foundation, counter-tweeted to explain that Ethereum has no “validation pools” at the protocol level. More importantly, Beiko suggests that the proof-of-stake hashing Levitin referred to is nowhere near as computationally intense as proof-of-work hashing. Therefore, it shouldn’t be categorized as “efforts of others,” Beiko argued.

Levitin’s validation

Once a security, always a security?

Ethereum was funded by an $18 million initial coin offering (ICO). Hinman implied in his 2018 remarks that ether may have been a security at its debut but by then had become sufficiently decentralized to where it was unlikely an investment contract anymore.

“Putting aside the fundraising that accompanied the creation of ether, based on my understanding … current offers and sales of ether are not securities transactions,” Hinman said.

Read more: Ethereum Launches Long-Awaited Decentralized App Network

If indeed ether was originally a security, couldn’t one make the argument that factors such as the extent of decentralization and the type of consensus mechanism are dials that move ether along a security-commodity continuum?

That would potentially strengthen Levitin’s argument that, although ether has achieved sufficient decentralization to be conferred commodity status, the switch to proof-of-stake could pull it back into the security zone.

Does the Ethereum Foundation operate like a software company?

A popular Twitter account recently posted a thread on how the Ethereum Foundation uses a so-called difficulty bomb to “coerce” developers into accepting hard forks initiated by the foundation. The “bomb” is a function that makes it exponentially harder to successfully mine ether on the original chain until mining becomes practically impossible.

Hard forks are network upgrades that are not backwards-compatible (you either accept the changes or split off onto a separate blockchain). Soft forks are changes to a blockchain that are backwards-compatible (you can continue using the network whether or not you accept the changes).

With a difficulty bomb hanging over their heads, miners have two choices – go along with the foundation’s proposed hard fork or start a new project (which also requires a hard fork).